Isabel and I became friends in seventh grade, and of all of my friends, her family’s ranch house in the Palisades might have been my favorite.

It wasn’t some sprawling behemoth. It didn’t have a pool or any fancy, modern touches. It was a standard one-story house. The living room had a massive wall of books, comfy seats, and patio doors that led to the backyard. There was a table where you could eat meals al fresco and a trampoline where you could talk about a crush—or, more likely for us, an enemy—in mid-air, gossip propelled out of our throats, breathy and bitchy with each jump. It was like an elevated boho hippie house. I’ll never forget the time I saw a book on the shelf with a binding that read FLUORIDE in huge font (before I even knew about fluoride freaks) or the moment I realized they didn’t have a microwave. My shock amused Isabel and her mom, but I didn’t see what was so funny about waiting 40 minutes for an Amy’s organic frozen lasagna to heat up in the oven. Still, it was these quirks that added to the charm of Isabel’s house. Whether we were 13 and watching Psycho at her birthday sleepover or 19 and catching up during winter break from college, Isabel’s house always enveloped me with this kind of California coziness that’s tough to replicate.

I loved Isabel’s childhood home. Right now, neither of us knows if it’s still standing.

Over the past week, I’ve met a few people who asked me where I was from. When I said LA, their eyes immediately softened. They asked if my family was safe, if I knew anyone impacted, and if I was okay. The answers were yes, yes, and eh.

Watching a series of fires rampage your hometown is enough to put you in a shit mood. The fires—most notably the Palisades and Eaton fires—have destroyed over 10,000 homes and claimed at least 24 lives, a number which is sure to rise. As of today, over 40,000 people have already applied for FEMA assistance. Hundreds of pets have been displaced and injured and are in need of immediate care. The air quality has been complete garbage, and I’m wondering if there will be a slew of ads in the next decade or two like there are here in New York for anyone who was in Manhattan south of Canal Street on 9/11 seeking legal compensation for their freaky cancer.

The Santa Ana winds picked up again last night after a period of relative calm, so the next few days might make it harder for firefighters to contain the fires. The firefighters are already working themselves to the bone, and some of those on the front lines are currently incarcerated and doing this brave work for very little money. Those who have lost their homes rely on strangers’ kindness via GoFundMe campaigns while landlords price gouge prospective renters1 and real estate vultures rub their hands like Birdman.

To top everything off, January is usually part of LA’s rainy season. There hasn’t been much measurable rain in the region for months, and it doesn’t look like that’s changing anytime soon. But rain would also be disastrous because a deluge of rain after a fire is the perfect combination for a mudslide.

So, yeah, I’ve been better. Texting a bunch of your friends who were either under evacuation orders or have lost their homes entirely is not how I expected to start the new year.

That first night, when everything started to get bad, my parents lost power. Slivers of smoke and the glow of flames from the Palisades fire were visible from their balcony, but not much else. They were far enough from the fires to feel safe, but the wind was bad, so bad I could hear it over the phone, and they could smell the smoke in the air. Their phones were dying, so they went to a friend’s house to charge up. I called them every 45 minutes, and they were so composed, such a contrast to the panic I was experiencing from my doom scrolling 3000 miles away, that I got annoyed. I spoke to them over speakerphone their entire car ride back home, reminded them to turn on low-power mode, and shared a thought that kept crossing my mind.

I grew up right along the Inglewood Oil Field, the largest urban oil field in the United States. Last year, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill that requires the oil fields to shut down by 2030. But I’ve long wondered what would happen if the fields were to catch fire. And now that wildfire season in California is no longer relegated to late summer and fall—it’s every season—how prepared would the city be to tackle such a blaze? How prepared would my parents be?

“Have you never thought about this happening?” I asked my mom. “Never?”

“Uhhhhhh,” she said, drawing the syllable out, not from concentration but, rather, alarm at my tone. “No?”

Oh. Okay.

There are other homes I know for a fact are gone, further up in the hills of the Palisades. There’s a house that once held a bedroom where I played Neopets and The Sims and a den where I witnessed a friend’s first kiss. Emily and I would take Razor scooters from her house down the hill into the village, pick up terrible direct-to-video horror movies from Blockbuster, and watch them when we knew her mom was asleep. I was last there when we were getting ready to see Panic! At The Disco in 2006 (I know). Sometimes, we went to this swing across the street from her house, a solitary swing that swung over the hillside and made you feel like if you jumped off, you’d land in the Pacific. In reality, you’d land in this terrifying thicket below, but if you didn’t look down, only looked ahead, it was just you and the ocean and nothing else.

Poppy’s house was up there, too, and somewhere else on some other winding Palisades street was Evan’s house, which I only went to once for an awkward eighth-grade birthday party. All I remember is that there was a pool, but I didn’t have a swimsuit, so I just rolled up my Dickies and put my legs in and felt like a fucking loser, and we all watched Night at the Roxbury later.

And there was this one time in high school when we had a half-day, and a few of us, including my old friend Jack, went to this fenced-off area up this hill near Emily’s house. We hiked up the hill a bit before plopping down on the dried grass and looking out at the houses below and the ocean in the distance. It was windy up there, and my skirt flew everywhere—coastal breeze. I needled Jack about his crush until my dad picked me up. It was one of those moments you have when you’re young, and you think, “Oh, this is what it means to be A Teenager, sneaking off to places you shouldn’t and talking to boys about stupid shit. Life starts now.”

Last Tuesday, I saw an Instagram story of the Palisades fire engulfing that hill in flames.

I watched this disaster unfold like I do all disasters now: My TV blaring CNN while I constantly refresh Twitter on my phone and scroll through news sites on my laptop. It used to be easier to get reliable news on Twitter before Elon came around; now, the algorithm makes it so that only a smattering of news shows up on my timeline while the relevant trending topics are littered with outdated info and reactionaries. I’ve seen more conspiracy theories than I’d like to admit: DEI hire lesbian firefighters unable to douse the flames, government laser drones, homeless tweakers, God taking revenge on Godless Los Angeles and Godless Hollywood following the Godless Golden Globes (I’m not linking to that peasant brained video), and, of course, the age-old “something something Jews something something.” Apparently, these things make more sense than “the fires were tough to fight due to hurricane-force winds and infrastructure issues” and “climate change is making fires worse.”

It’s unsurprising that people are using this wildfire as a vehicle for their ignorance and cruelty, but it’s still hard to stomach. I’ve seen enough right-wing nutjobs sneering about California, the so-called failed state, to last a lifetime. But I’ve also seen others seemingly convinced that good leftism means lacking empathy toward people who lost their homes if their homes were worth a lot of money. It’s alarming to know that so many people are so deeply stupid.

At least there appears to be no ideological divide in characterizing Los Angeles as a land of celebrity and excess, of brainless denizens walking around in workout gear, buying a $40 green juice at Erewhon after reiki, and hopping into their expensive cars en route to their mega-mansions. Sure, we have people like that—and I still don’t think they deserve to lose all their possessions in a fire—but my point is that these are largely stereotypes that flatten Los Angeles into this shallow place I don’t recognize. Maybe it’s because I was born and raised there, but that has never been my Los Angeles.

Most Angelenos are normal people living normal lives, paycheck to paycheck. Even the entertainment industry—the only industry that seems to exist in Los Angeles according to these cynical outsiders—is held together by the work of working-class technicians, exploited writers, and union workers clocking in and out like everyone else. The glitz and glamour keep things interesting, but that alone doesn’t define Los Angeles.

I don’t want to go into some purple diatribe about how Los Angeles is a place of contrasts—“LA is a land of mountains and beaches, of Nobu and taco trucks” or something equally trite—but it is, and that’s what makes it the rich, dynamic cultural tapestry that it is. Of course, like anywhere else, Los Angeles has plenty of flaws. It’s just that Angelenos already know all that, and nobody else knows Los Angeles like we do.

The media hasn’t helped fight this false perception either. So much of the coverage, especially on cable news networks, especially in the early days of the fires, focused primarily on the impacted parts of the Palisades and Malibu. Essentially, the whiter and wealthier part of town got more coverage than the less affluent, more diverse (read: blacker, browner) one with a rich black history born from redlining and white flight. Yes, the Palisades fire happened first, and it’s the most ferocious of the lot. But hearing reporters emphasizing its pricey real estate and expensive beachfront properties and the celebrity residents ad nauseam? Overkill. Tacky.

Was the middle-class (though rapidly gentrifying) neighborhood of Altadena on the other side of town, left decimated by the Eaton fire, simply not sexy enough to warrant as much attention?

And still, it’s worth mentioning that while the Palisades was home to wealthy residents, many other residents aren’t so lucky and won’t be able to rebuild any time soon, if at all. Home prices have grown much faster than people’s incomes, so, for many, whatever wealth they had was wrapped up in the value of the home they bought more than 30 years ago.2 And now it’s gone. There were also regular middle-class residents and renters, as well as non-residents who lost their jobs in the service industry, education, childcare, landscaping, etc overnight.

Both the Palisades and Eaton fires have left generations of Angelenos homeless with nothing but the clothes on their backs. They didn’t just lose their homes; they lost family treasures and irreplaceable personal keepsakes.3 And now they’re in insurance hell. They will require emotional support, financial resources, bolstered social safety nets, and protection from capitalistic forces that do not see them as human beings but rather as entities from which to extract money, even at their lowest moment.

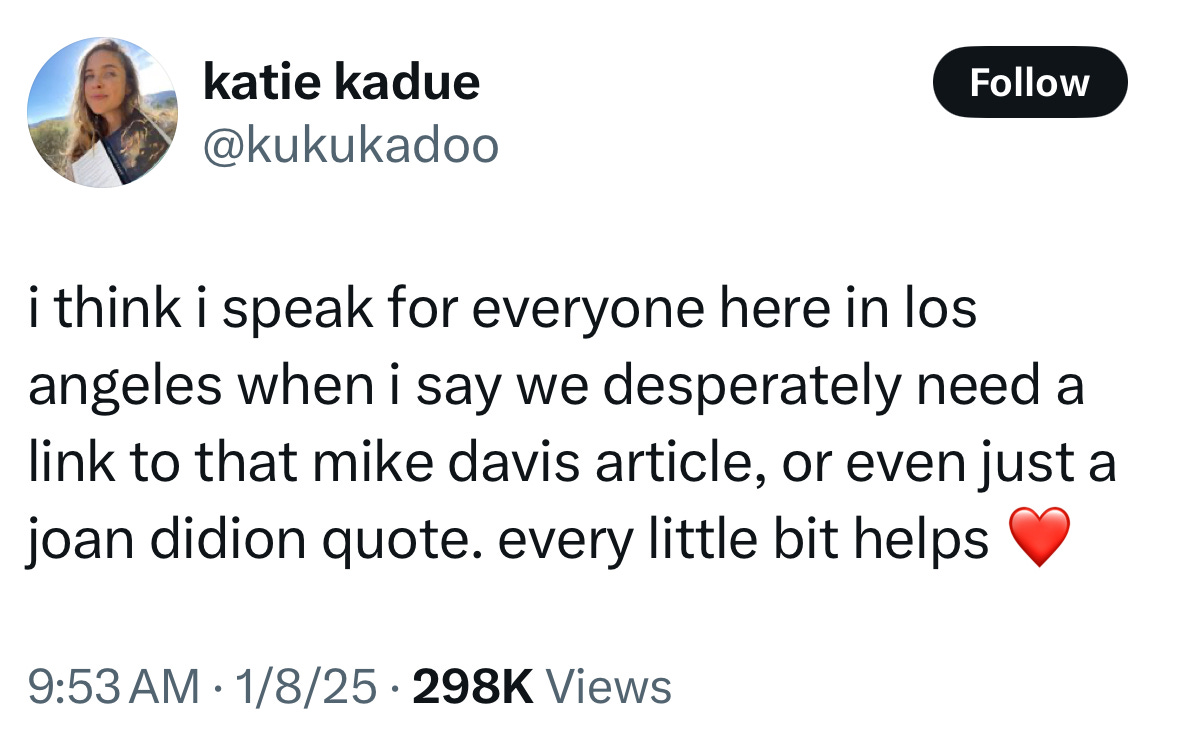

I’ve already gone on too long, so I won’t even touch on those condescendingly concerned about the state and future of Los Angeles. I’ll emphasize a tweet I saw by writer Katie Kadu and say…I don’t think Angelenos, especially ones who have lost everything, need to see another Joan Didion quote about the Santa Ana winds or another contextless link to Mike Davis’s “The Case For Letting Malibu Burn.” We can reflect and investigate how we got to this point without a pseudo-intellectual circlejerk from people who don’t even know someone who lost their home.

(Besides, if we’re going to take lessons from eerily prophetic works, let it at least be from the late sci-fi writer and Altadena resident Octavia Butler. Her book Parable of the Sower imagined a post-apocalyptic Los Angeles ravaged by economic disparity, racial division, and, yes, climate change. There’s even a fire if you want to drive the point home. I’ve read a little Butler in my time, and while sci-fi isn’t my thing, it is undoubtedly an effective way to talk about contemporary ills. I’m adding it to my ever-growing to-read pile, behind all the books about loss, illness, and widowhood I’m still getting around to. You know, the fun stuff.)

I think about permanence a lot; the idea of it, how nice it sounds on my tongue, even though I find its concept mocking. Seeing people experiencing the destruction of their homes—a slice of permanence—is gutting, especially when it hits so close to home. It’s made me take stock in what is truly valuable to me, the irreplaceable things I’d grab in a hurry in an emergency. It’s also just made me even more empathetic to those we’ve also seen lose their homes before our very eyes, namely the people of Gaza. They also had irreplaceable keepsakes, pets, and rooms where first kisses were had.

If there’s one positive thing that has come out of this tragedy, it’s that I’ve seen so many people wanting to help. People are donating to families in need, sharing mutual aid networks, and volunteering on the ground and remotely to help Angelenos. I’ve lived in New York City for nearly 12 years now, but Los Angeles is my original home, and I love it even more today than I did a week ago, especially after seeing us pull together to care for our people.

Rob always joked that LA is a desert hellscape. Yeah, but it’s my desert hellscape, goddammit.

Donate and/or share, if you can:

The National Day Laborer Organizing Network’s Immigrant Fire Relief Fund

Altadena Girls: Restoring Normalcy For The Teenage Victims of the Eaton Canyon Fire

Here’s the Tracking Rental Price Gouging in LA spreadsheet

It’s the same thing in my neighborhood in Brooklyn: Middle and working-class families own brownstones now worth millions of dollars, but that doesn’t mean they’re making a lot of money.

I was gutted when I saw an interview of a woman who wasn’t able to save a loved one’s ashes in the fire; what a nightmare.

This was searing and beautiful, Ashley. You took me straight into the living rooms, swing sets, and Blockbuster nights of your LA—then lit the whole thing on fire with grief, rage, and clarity.

What hit hardest was the line about permanence feeling like a mockery. That ache of watching spaces that shaped you vanish overnight—rooms where you first felt like a person—feels primal. And it’s so true: those keepsakes, that sense of place, it’s not about money or square footage. It’s about meaning. Memory. The stuff that makes us.

Also, thank you for calling out the lazy stereotyping of LA. I’m not from there, but I’m so tired of the caricature version—like the real people who cook, clean, commute, and build culture don’t matter unless they’re name-checked in a TMZ chyron.

You managed to make this a personal essay, a political critique, and a love letter all in one. LA is lucky to have you as one of its voices—even from across the country.

(And yes, we need more Octavia Butler, less Didion-at-parties energy right now.)

Holding space with you and everyone hurting right now.

The havoc seems very intense & implacable. The blog tuned into dewy-eyed & amour. I hope this dismay is not foreseen in as dantes inferno!! Condolences